Heap Interval

Published on Aug 15, 2024

Introduction

In my previous post I gave a brief introduction to interval arithmetic and applying it to solidity. Instead of going one by one through various different mathematical operations over intervals, I want to switch gears and focus on intervals of memory/heap allocated values.

Solidity Memory

Quickly, there are 5 locations values can be stored in the evm:

- Stack: queue of 32 byte words

memory: nonpersistent contiguous mutable byte arraycalldata: nonpersistent contiguous immutable byte array controlled by callertransient: nonpersistent mutable mapping of a slot to a valuestorage: persistent mutable mapping of a slot to a value

This effectively means that most values that require >= 32 bytes must be allocated someplace other than the stack.

For mapping-style locations, we can define an initial offset that is extremely unlikely to collide with any other

possible offset by running a hash function over some unique key (i.e. keccak256("my.array.storage.slot")) – the solidity

compiler does this automatically for you by assigning a numeric slot to each storage variable. After defining the initial

offset, you can just increment the slot by 1 for each word stored. Maybe I’ll make another post on how this all works

with some nice graphics but not today ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

note: technically, with EIP-663, the compiler could make use of the stack for larger values by spreading the data across words on the stack and swapping more liberally but this seems unlikely to occur

As a brief refresher on memory/heap values in solidity, there are a few types that are represented in heap form:

- arrays (

uintX[],intX[],bytesX[],MyStruct[], etc.) - structs (

MyStruct) - mappings (

mapping (X => Y)- storage only)

Each of these can be specified to be stored in different locations:

calldata- i.e. offset insidemsg.datamemory- i.e. offset inside the evm’s memorystorage- i.e. offset in contract storage- (not yet available)

transient- i.e. offset in transient storage

Representation in Interval Analysis

There are a few ways to model these heap-like objects. I’ll first describe how I model them in pyrometer, then another (potentially more intuitive?) way, and finally how to get the best accuracy you actually want both models.

Let’s start with a calldata allocated uint[]:

function echoArray(uint256[] calldata x) public pure returns (uint256[] calldata) {

return x;

}Think about how you might represent this – ask yourself important questions about what the data could look like:

- What’s the length of

x? - What operations may take place on top of

x?

The answer to these two lead me to the following representation:

Effectively, we have a length represented by a uint256, and a mapping of keys (in the domain of the mapping’s key or uint256 if an array) to values

(in the domain of the array’s or map’s inner type – i.e. uint256[] -> uint256, or mapping (address => bytes32) -> bytes32). I’ll talk about why

this representation is cool later.

The other way you can represent heap objects is to actually implement a sort of meta-heap object using the same construction as above, but instead

of the object itself being represented, we construct a bytes1[] that represents memory and calldata with memory objects being split up and assigned into

this byte vector. This model has a few downsides, notably if we don’t have tight bounds on where in the byte vector a heap allocated object is being

stored, we lose a ton of information that we could have kept around. For example:

function bytesVectorApproach(uint256[] memory x, uint z) public pure {

uint[] memory y = new uint256[](z);

x[z] = 5;

y[z] = 5;

}With the bytes vector approach, we have no information on the size of x or y and the value of z. Deconstructing this example, x is initiated and put into the

bytes vector as having any value any place in the bytes vector after 0xa0 (because x’s length is undefined and user controlled, and solidity stores memory objects

starting at 0x80, with the first word of an array being its length). Once we construct y with length z, we have gained no new information because we didn’t know

the size of x. When we assign x[z] = 5 and y[z] = 5, z is unconstrained as well so every value after 0xa0 could now be 5 - but that was already in the range

of every byte in the byte vector, so again more information is lost.

But the benefit of the byte vector approach is that yul/assembly mload & mstore operations are more easily supported.

The independent object approach is interesting because when you index into the object, the keys/indices are intervals. Here is an interesting example:

function nestedBytes(uint y) public pure returns (uint) {

uint[] memory x = new uint[](3);

x[0] = 15;

x[1] = 5;

x[2] = 25;

require(y < x.length);

return x[y];

}We would represent x as having a length of 3, and three set indices: [0, 1, 2]. Each of those indices have a concrete value, (15, 5, and 25 respectively).

With the requirement that y < x.length, when we perform x[y], we do a comparison of y against all the keys. This comparison is an “overlap” test - where we

check if the ranges intersect each other:

The yellow lines are the minimums, the green lines are the maximums.

Overlaps are an important part of interval analysis. They let us build up logical

operations like [<, >, <=, >=, ==, !=], etc. These aren’t traditional boolean comparators,

but more “fuzzy” comparators - they compare if it could be true not if they are exclusively true.

So when we compare y to the indices of x, we find that it could match [0, 1, 2] (all indices), so the range

of x[y] is [5, 25] (or [x[1], x[2]]). That’s what makes this representation so cool!

It makes it easy to find possible values of a heap object.

So the best model is actually something like:

- Represent each memory object independently

- Model solidity memory allocation rules to define the possible offsets of individual memory objects

When we construct a heap object, we can assign it to an index of a special array that represents the heap. In normal solidity usage,

it won’t really be needed, but if a contract performs mload, one would:

- perform overlap tests on each index’s interval against the passed in location

- for each matching index, we get the value (a heap object), and calculate any remaining offset to load from inside that object

and we now have decent interoperability between independently modeled heap objects and low-level memory access!

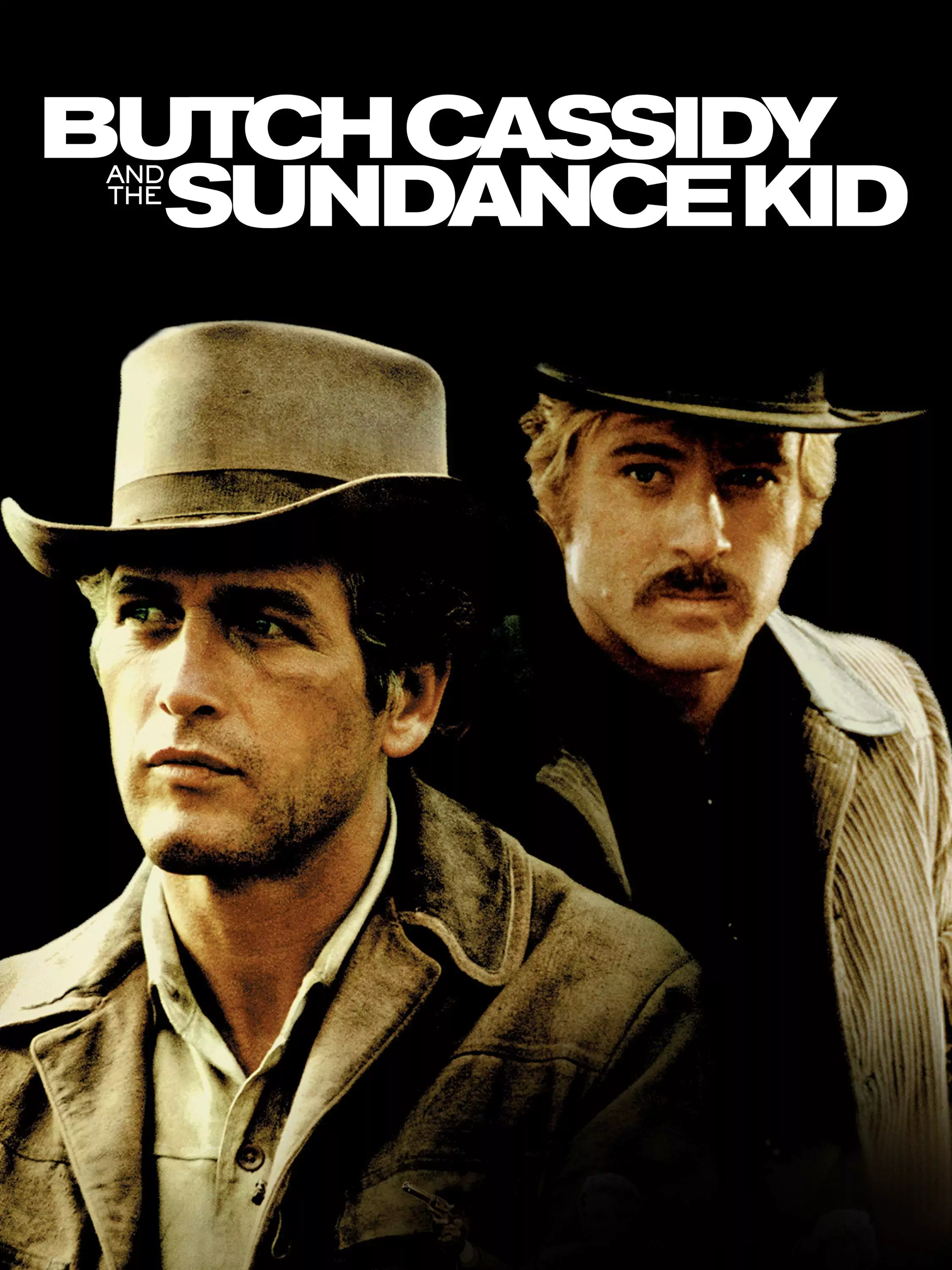

Movie Recommendation

Okay, that’s all for today. This week’s movie recommendation is Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. 9.1/10